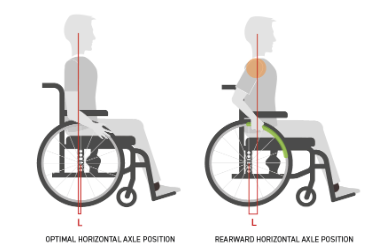

Wheelchair biomechanics is the exploration of how a wheelchair user imparts power to the wheels to achieve mobility, and helps us understand how the user’s body interacts with the wheelchair (McLaurin and Brubaker, 1991). The configuration of the wheelchair, specifically where the wheel axle is positioned in respect to the user’s center of mass, will greatly influence the range of motion that is required of the shoulder joint for propulsion. Too far forward and balance is compromised, too far back, and the user will be required to max out their shoulder extension range of motion. When the axle is too high you’ll get excessive elevation. Repeated over thousands of strokes and you could begin to understand why anterior shoulder pain, or impingement, is common. So the first order of business, and one that fitness professionals won’t particularly be involved in but should be aware of if a client complains of discomfort, is proper configuration of the chair.

(The Path to Perfect Propulsion – Tips and advice, Motion Composites)

Like gait, the inter- and intra- movement variability will be high. Universally, however, there are two phases of propulsion: the push phase and the recovery phase.

Push or Propulsive Phase – when the hand comes in contact with the push rim until the point at which the stroke is completed and it loses contact

Recovery Phase – the period of time between when the hand is released from the push rim at the end of the push phase to when the upper extremities swing back for the next propulsive phase

Many users strive for the push phase and recovery to be of equal duration. There are typically four common propulsion techniques. They vary in where on the push-rim the hand comes in contact but predominantly in how the hand moves through recovery.

The semicircular pattern is often encouraged for its biomechanical efficiency: lower stroke frequency, more time in the push phase, and less extraneous movement through the hand and shoulder. It’s considered to be the most efficient technique for level ground and the range of 10 o’clock to 2 o’clock is within a mechanically advantageous position for the shoulder that doesn’t require us to repeatedly load end range of motion.

The arc stroke is considered to be most efficient for traveling uphill but less so on flat ground. The reduced stroke length lessens momentum and constant contact with the handrim essentially functions as a braking force. But the consistent contact with the rim prevents the chair from rolling backwards, which is why it’s recommended on uphill climbs.

Single loop over has a different recovery strategy than the arc, passing above the push rim. It’s believed to be both an inefficient stroke, since the starting point tends to fall closer to 11 than 10 o’clock so range of motion is reduced, as well as an unhealthy one long term due to the fact that it encourages excessive elevation and extension.

In the Double Loop over pattern initiates the recovery in a similar way to the SLOP, before letting the hands fall below the push rim and following the semicircular pattern. Some studies have shown that many wheelchair users default to this pattern.

The literature suggests that using a lower cadence (Mulroy et al., 2006; Rankin et al., 2012), increased contact angle (Mulroy et al., 2006; PVACSCM, 2005) and increased contact percentage (PVACSCM, 2005) can lead to reduced strain on the upper extremities and a lesser likelihood of shoulder pathology and pain. decreased demand on the upper extremity and the likelihood of developing pain and injuries. Current clinical guidelines recommend the use of SC, citing many potentially advantageous levels of these biomechanical metrics (PVACSCM, 2005) including the decreased cadence and increased contact angle. While the semicircular pattern is recommended, research shows that users are most efficient when they self-select a push frequency (Goosey et al, 2000).

User education is essential to ensure that faulty biomechanics doesn’t increase the likelihood of injury. Research shows that guided and focused repetition, in this case, nine 90 minute sessions for six participants with a SCI, can improve propulsion patterns for new manual wheelchair users. (Morgan et al, 2017). It is likely that you personally won’t be responsible for this education; but being aware of the importance will allow you to more effectively support your clients.

If you’re interested in diving more into this topic, check out our course “Improving Upper Extremity Health in Manual Wheelchair Users” in the AdaptX educational curriculum.